New York’s newly elected Mayor, Zohran Mamdani, recently made headlines with the memorable quote from his inaugural speech claiming that he would replace the “frigidity of rugged individualism with the warmth of collectivism.” This statement spurred immediate backlash from notable figures such as Bishop Robert Barron, who responded in a tweet:

“Collectivism in its various forms is responsible for the deaths of one hundred million people in the last century. Socialist and communist forms of government around the world today – Venezuela, Cuba, North Korea, etc. – are disastrous. Catholic Social teaching has consistently condemned socialism and embraced the market economy, which people like Mayor Mamdani caricature as ‘rugged individualism.’ In fact, it is the economic system based upon the rights, freedom, and dignity of the human person. For God’s sake, spare me the ‘warmth of collectivism.’”

In his address, Mamdani appeals to a felt reality shared by many young people. Loneliness and isolation plague our modern world. Loneliness and isolation are frigid, but this is not the same as rugged individualism, and the state is not the solution to this malady.

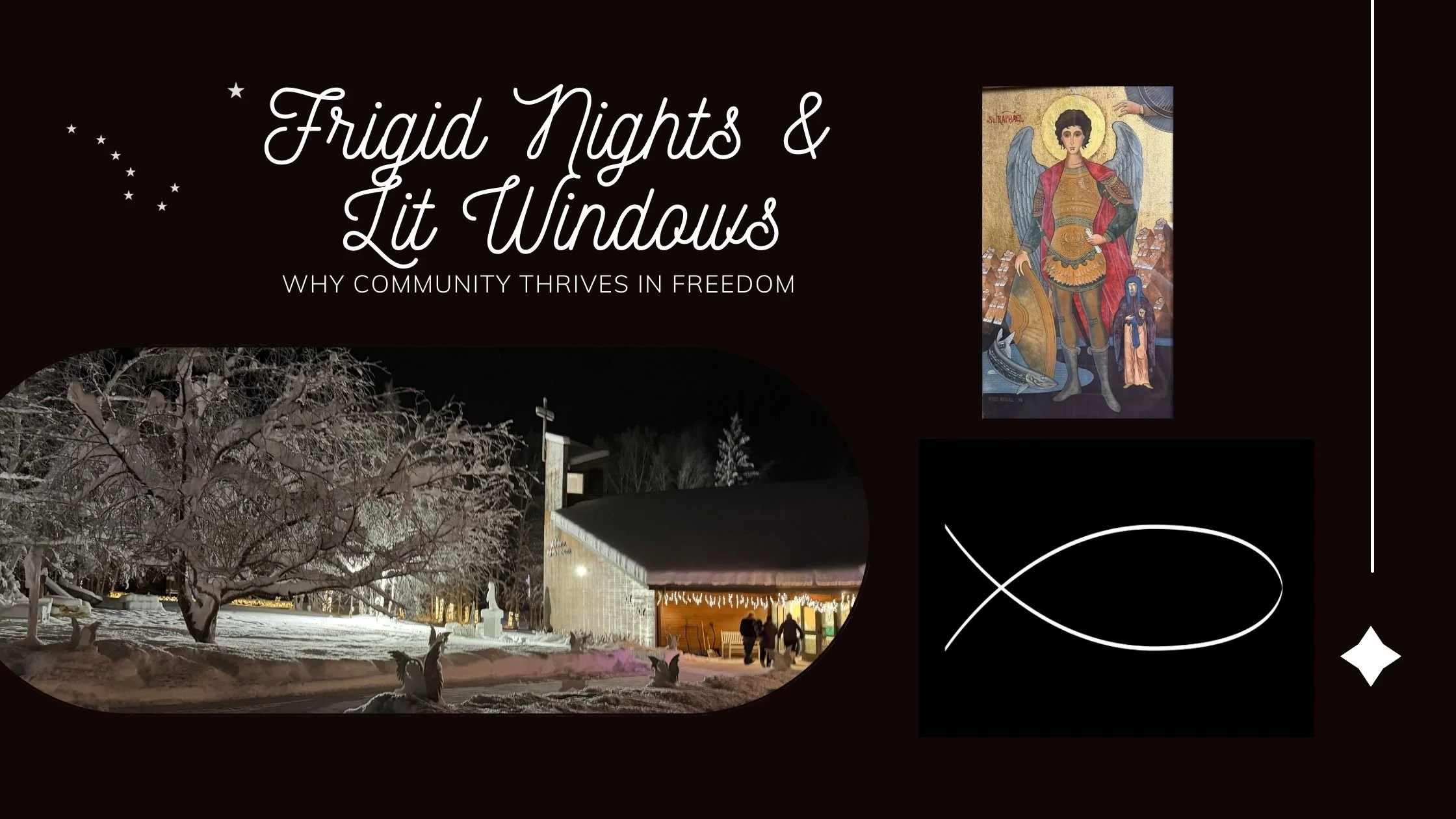

Working in Alaska has given me a few experiences of frigidness and rugged individualism. This state magnifies the contrast between isolation and community. I have found that many search for a taste of this isolation, seeking a “retreat” from the fast-paced world. I have been blessed to lead a few retreats around the state and to walk with women seeking wisdom in this time away. Recently, I found myself deep in the interior of Alaska, on the outskirts of Fairbanks, on a long stretch of dark road in the Alaska wilderness, headed towards one of these short retreats. A snowstorm made visibility challenging. There were no distant city lights visible. For a moment, I felt the vastness of the wildness around me. I felt engulfed by the dangerous sublimity of the unforgiving winter space. Then the road approached a small, lit-up structure. St. Raphael shone bright, tucked away in the forest, emitting a warm, inviting glow. It was not a grand Cathedral with spires lifting one towards heaven; it was a simple shelter bordered with small Angelic statues, evoking safety, protection, warmth, and community. A few men could be seen inside, gathered around a table, sipping coffee and deep in conversation.

Alaska often provides this natural chiaroscuro. The harshness of the environment, the long gaps between settlements, remind one of both the resilience and limitations of independent man. Community stands as a beacon and an oasis of safety. Light and warmth flood in overwhelming abundance after an extended caesura. This warmth, however, requires the effort of man.

As the retreat began, women straggled in, some from far-off settlements, each with their own story, they came of their own will, seeking. As the day continued, we joined together in prayer, in conversation, and in true communion. We all left slightly changed by the experience. While I was technically leading the day, my main task was to point the women toward Christ, the one who truly knows their hearts, to each other, and to give them tools of reflection, conversion, and fortitude. We all left in freedom to answer the call placed on each of our hearts.

No one can truly make it alone in a place like Alaska. Organic communities form and are free to do so. In this case, it was a retreat at a church. The day before, I attended a festival tucked in the basement of another church, with food, dancing, and stories. This is the warmth of community.

St. John Paul II lived firsthand the false promises offered by the warmth of a state-run collectivism. He wrote extensively on the properly ordered relationship between the individual and the community. His principles are worth revisiting. The Catholic theology of community has embedded within it an awareness of the importance of the teleological end of each individual person within that community and the need to allow each person the freedom to assent to that end.

Dystopian novels are riddled with imagined perfected futures that achieve the common good through force and the removal of choice. The freedom of men provides a pathway for all manner of sin, pain, and tragedy to enter the world. This is the great paradox of love. Love cannot exist without freedom, but freedom does not guarantee love. When I peek out into the wider world beyond my small community, I am tempted to be overwhelmed by the chaos. There is much pain echoing throughout the world. Rather than pull at levers beyond my reach, I believe that the best thing I can do is set my gaze upon Christ, set my face like flint, and continue to look for the daily demands love asks of me. I am simply one individual, but I have the freedom to seek community, to build community, and to be nourished by and through Christ-centered community.